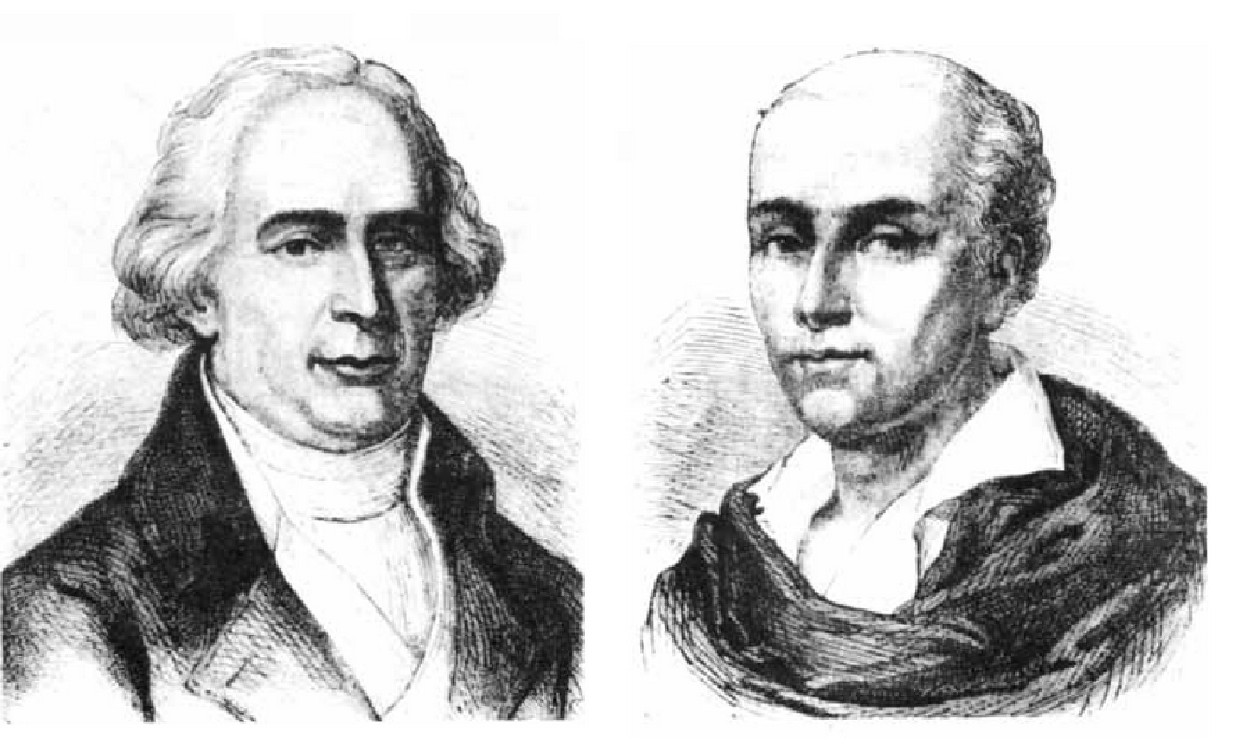

On September 19th, 1783, at the royal palace in Versailles, Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Etienne Montgolfier introduced the King and Queen of France to their redoubtable 500lb invention, a curious brightly painted contraption of sackcloth and paper, wrapped in a fish net and held together with buttons.

Their ambitious intent was to position the bag over a fire, fueled with bundles of chopped straw, and inflate it into a balloon, which would then be manned by a sheep, a duck, and a rooster and raised into the sky, achieving the world's first ever flight with living creatures.

To the delight of the crowd, and the King and Queen, their endeavor was successful. The balloon was inflated to a diameter of 36 feet and made to fly a distance of 2 miles in just over 8 minutes. Moreover, the bewildered passengers were neither suffocated, as it was presumed they might be, nor in any way damaged. Rather, it could be said easily, they were elated.

In the mid-eighteenth century, pneumatic chemistry was making a comeback. Research from prominent scientists, like Joseph Black and Henry Cavendish, led to the discovery of more than seven gasses that differed in property and behavior from air. It was no longer possible to promote with certainty the theory of Phlogistein, which, among other things, stated the four elements could be transformed from one into the other, and that air was one of these 'elementary constituents of matter.'

It's no wonder then that Joseph Montgolfier, the more recluse and imaginative of the brothers, called the substance that when heated propelled the balloon into the air, "Montgolfier Gas."

Later in the century, after multitudes of balloon flights, and exhaustive research into the physical composition of air, it was determined decidedly that air when heated rises.